In December of 2019, I looked forward to setting and smashing my 2020 genealogical goals. Then COVID happened. While the rest of the world seemed to slow down, my life seemed to get busier! Between work (a paying full-time job that’s not related to genealogy) and volunteering with various organizations, it didn’t leave much time for the love of genealogy and telling the stories. Every genealogist loves to tell a story!

For 2021, my biggest goal is to tell those stories and I will be doing so with Amy Johnson Crow’s 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks. What I write about may be an ancestor or part of the historic project I’m working on for our local Kings Road Historic District.

2020 ushered in the age of virtual learning. It looks like 2021 will continue that way and I’m looking forward to GenProof, IGHR, BCG Study Group, and anything else that pops up!

Beginning Again

Beginning again is never easy and it’s something our ancestors did over and over, whether moving to a new country, a new state, a new county, or even the next town over.

Historically, Florida has been the state for starting over. It was a stop for wayward travelers from Portugal, France, and Spain. The Spanish claimed the land for themselves and so began the land of new beginnings.

As the Europeans jockeyed for control over the peninsula, La Florida changed flags several times. Governments changed, laws changed, and land ownership changed during these years.

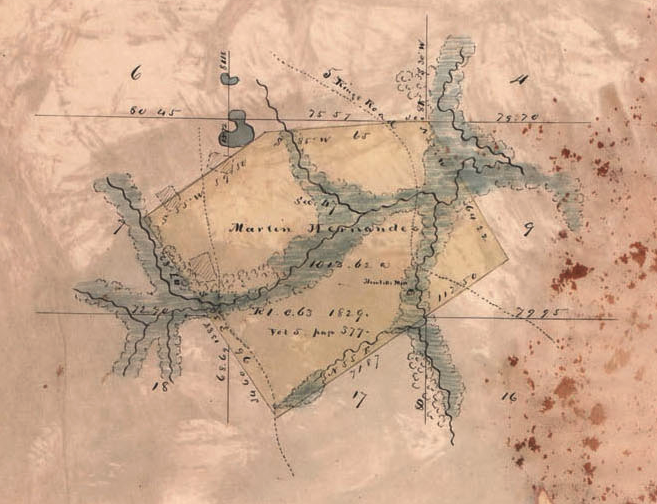

While doing research for the Kings Road Historic District, I am completing a one-place study, starting with the land ownership of the area we are researching. This land is still known today as the Martin Hernandez Grant.

Before the Europeans came, this land belonged to the tribes that would become known as the Timucua. Timucua is the language that united the tribes along the St. Johns River valley. It is likely the tribes Utina, later known as the Agua Dulce, and the Mocama used this land for hunting.

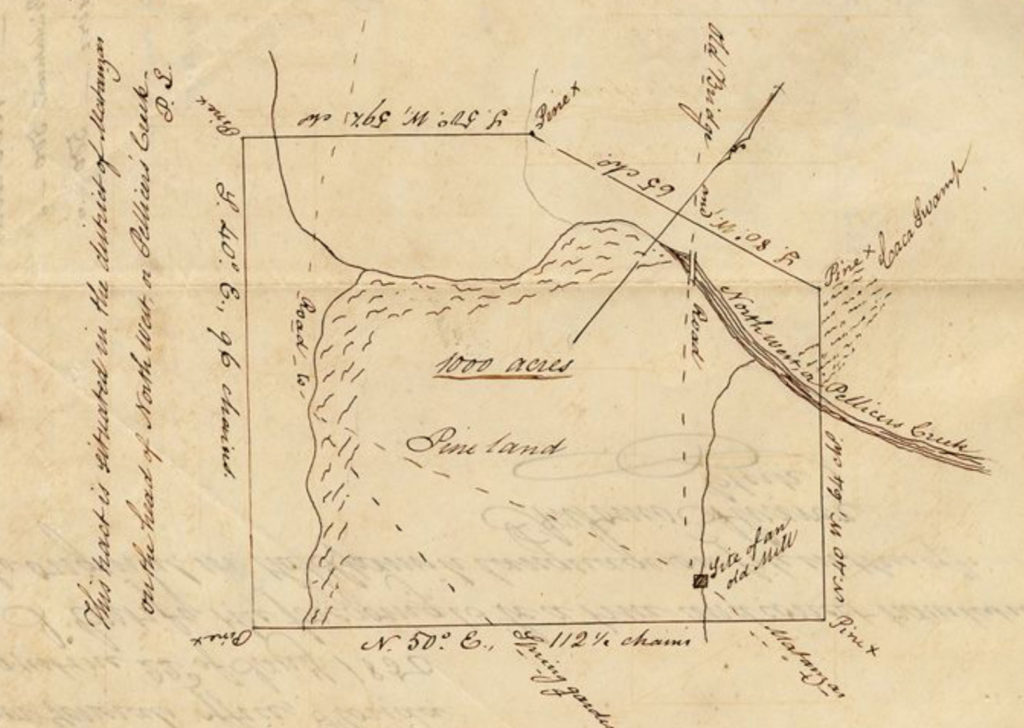

There were three roads and a creek with tributaries in the pineland plat. What became known as the Kings Road and Spring Garden Road during the late 1700s and early 1800s, were formed from Indian trails. The Northwest or Pellicer Creek, would have provided prime fishing as well as hunting in the pine forest, as they still do today.

Spanish Florida (1565-1763)

When the Spanish claimed all of the lands, it became the property of King Philip II. During this time, private property only existed by the right of royal grant or concession. The first grant, which included the Martin Hernandez Grant, was given to Don Pedro Menéndez de Avilés in March of 1565. It included twenty-five square leagues (110,710 acres).

After Menéndez’s death in 1574, the land went to his immediate successor Hernando de Miranda. Miranda was Menéndez’s son-in-law and he attempted to continue the colonization of the area. By 1600, King Philip repudiated all property in La Florida and the Martin Hernandez Grant became the King’s property once again.

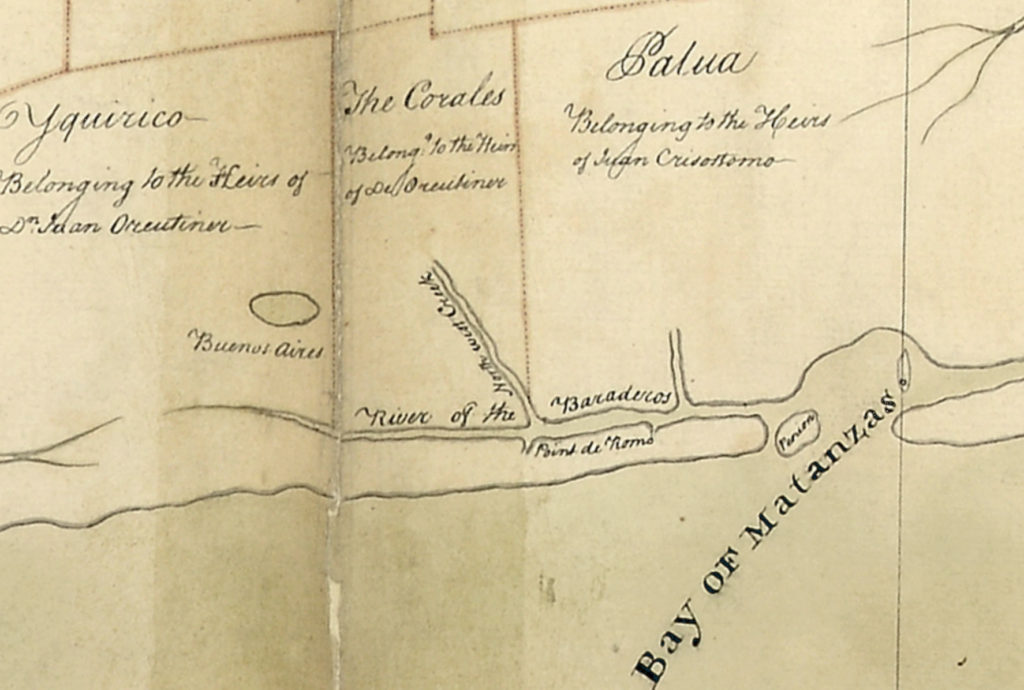

The laws on land ownership of San Agustín and La Florida depended on the Recopilación de Reyes de los renos de las Indias. Floridians could petition for land but the Royal and Supreme Council of the Indies ignored or refused requests. This led the governors of Florida to grant lands illegally, “in the name of the king.” One of those lands was known as Los Corales and belonged to the heirs of Don Juan Oreutiner. It is unknown if any agricultural activity took place on Los Corales.

Eventually, land petitions were approved and the property was given based on the social status of the grantee. Many stipulations were connected to the land grant and the crown could revoke that land at any given time. These were smaller pieces of property, known as peonías and caballerías.

As Spain ceded Florida to the British Crown in trade for Havana in the Treaty of 1763, John Gordon and Jesse Fish purchased the illegally granted land from the Spaniards during 1763 to 1764 from the Spanish Crown’s official realtor, Don Juan Elixio de la Puente.

Jesse Fish was known to the Spanish Crown as he lived in San Agustín prior to 1763. The market to sell the land was abysmal, so Puente entered into an agreement with Fish, where Fish would become the owner of these lands and resell them at a later date when the market was better, passing on the proceeds to the owners while keeping some of the profits for himself. Their entire transaction was illegal and would have been considered treasonous if caught!

The British Crown was suspicious of the landholdings of the Gordon-Fish partnership. James Grant, the first Governor of East Florida, did not believe they could have obtained 4.5 million acres of land from Spain. By 1768, the land was being distributed to petitioners, while Gordon struggled to win the rights to the land through the British Parliament in London.

British Florida Period (1763-1783)

The Loyalist John Hewitt was granted land that likely included all of or part of the Martin Hernandez Grant in 1775, where he built a profitable sawmill. The Surveyor General, William Gerard de Brahm, observed a place fit for a mill, which was located on what he called Little Matanza River, also known as Northwest Creek and Pellicer Creek.

John Hewitt was a well-known carpenter in the area and his mill provided wood for Saint Augustine as well as Forts St. Mark, Picolata, and Matanzas. He rebuilt the bell tower at Trinity Episcopal Church and worked on the Governor’s House, with wood from his mill. The area that grew from this mill became known as Matanzas.

It was during this time the Kings Road was being built, to connect Saint Augustine (San Agustín) and Mosquito (New Smyrna), providing a 75-mile road connecting the two areas and some plantations along the way. Governor Grant believed these public works would help open the land up for additional settlement. Ten years later, this growth and expansion would revert back to the Spanish Crown.

Second Spanish Period (1783-1821)

The 1783 Peace of Paris accord officially ended the American Revolutionary War and the Treaties of Versailles ceded Florida back to Spain. By this time John Hewitt was deceased as his widow Sara and small children left in 1784, on the emergency transport ship Charlotte bound for Bermuda. His minor son Thomas Hewitt made claims on his father’s properties in 1787.

A census of Saint Augustine was conducted, up to five leagues outside of the city, in December of 1786. Under the heading of Menorquíans, Italíans, Greeks and Others Known as Such, Martin Hernandez is listed with his wife Dorotea Gomilla, both of Menorca, and two daughters, both of San Agustín. Hernandez was part of the Menorcans who were indentured to Andrew Turnbull and his plantation in New Smyrna. They were promised land in Florida for their servitude but legally, they would never be able to receive any due to their religion. Under British law, Catholics could not own land. The indentured people suffered greatly under Turnbull and in 1777, they desperately escaped to San Agustín.

The Hernández’s, like most of the refugees from New Smyrna, stayed on in Saint Augustine when the British Loyalists left. The British-style plantation system remained in place and some plantation owners transitioned to Spanish rule.

Hewlitt’s Mill and the area surrounding the Martin Hernandez Grant was most likely occupied from 1783 through 1812. This turbulent time period had the area residents dealing with invasions from the north, culminating with the Patriot War from 1812-1814. It is thought the mill burned down during the Patriot War as nearly every farm and plantation was burned or plundered by the American invaders in East Florida.

After the Patriot War, the Spanish knew it would not be too long until Florida was annexed into the United States. They began to distribute land grants to veterans who served in the war. Martin Hernandez was living in Cuba by 1817, when his oldest son, Jose Mariano Hernandez, applied for 2,000 acres in his name. The elder Hernandez served as the Chief Master Carpenter for the Royal Fortifications and was eligible for a land grant. One thousand of those acres was located at the head of Pellicer Creek.

Jose Mariano Hernandez, later known as Brigadier General Joseph Marion Hernandez, may have requested that specific acreage as it was very near to his own land, on water, and would have provided a place for a mill to his substantial holdings. By 1821, Joseph Hernandez had amassed 25,670 acres through land grants, service grants, headright grants, and purchases in Florida.

Territorial Florida (1821-1845)

Florida was finally annexed by the United States through the Adams-Onís Treaty in 1819 and officially ceded in 1821. The Territory of Florida was the 3rd new beginning for Florida and its people in less than 60 years. It would take another 24 years for Florida to become a state.

The United States agreed to honor the Spanish land grants but residents had to prove the ownership through documentation and testimonials. The Commission of 1828 confirmed the Martin Hernandez Grant of 1,000 acres in Matanzas.

Martin Hernandez never came back to Florida and died in Havana, Cuba. At a later date, I’ll tell the story of the many, many owners between Territorial Florida and Statehood, through the Seminole Indian Wars, Civil War, and into the Twentieth Century.

Resource List

Books

Julian Cranberry, A Grammar and Dictionary of the Timucua Language. 3rd ed. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1993.

James G. Cusick, The Other War of 1812: The Patriot War and the American Invasion of East Florida. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003.

Lawrence H. Feldman, The Last Days of British Saint Augustine, 1784-1785. Baltimore, Maryland: Genealogical Publishing Co, 2003.

Robert L. Gold, Borderland Empires in Transition: The Triple-nation Transfer of Florida. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1969.

Melissa N. Hagen and Carl D. Halbirt, “The Hernández Orange Grove: A Nineteenth-Century Enterprise in St. Augustine, Florida,” Paper for the 57th Annual Meeting of the Florida Anthropological Society, University of Florida, 2005.

William Jones, “A British Period Water Sawmill, Flagler County, Florida,” El Escribano, Vol. 18 (1981).

Nick Linville, “Cultural Assimilation in Frontier Florida: The Life of Joseph M. Hernandez, 1788-1857,” MA, non-Thesis paper, University of Florida, 2004.

Donna Rachel Mills, Florida’s First Families: Translated Abstracts of Pre-1821 Spanish Censuses, Volume 1. West Minster, Maryland: Heritage Books, Inc, 2011.

William P. Ryan, The Search for Old Kings Road. Palm Coast, Florida: Old King’s Road Press, 2006.

Wilbur Henry Seibert, East Florida as a refuge of southern loyalists, 1774-1785. Worcester, Massachusetts: American Antiquarian Society, 1928.

Wilbur Henry Siebert, Loyalists in East Florida, 1774 to 1785 1 : the most important documents pertaining thereto. Deland, Florida: Florida Historical Society, 1929.

St. Augustine Historical Society, “Hernandez Family Biographical File.” Folder 1. Vertical Files. St. Augustine Historical Society Library, St. Augustine, Florida.

Dana Ste. Claire, True Natives: The Prehistory of Volusia County. Daytona Beach, Florida: Museum of Arts and Sciences, 1992.

Maps

“James Moncrief, ‘Map of Part of East Florida from St. John’s River to Bay of Mosquitos,’ [1764],” MapScholar (http://www.viseyes.org/mapscholar/?1824 : accessed 15 Dec 2020); CO 700 / Florida 7, The National Archives of the UK, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, UK, http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C3477616.

John and Samuel Lewis, “A Plan of part of the Coast of East Florida,” 1769, MapScholar (http://www.viseyes.org/mapscholar/?1824 : accessed 15 Dec 2020); The British Library, London.

Websites

“Dispatches from John Moutrie to the Earl of Dartmouth, enclosing Council minutes,” database with images, Colonial America (http://www.colonialamerica.amdigital.co.uk/ : Accessed 14 Dec 2020), entry for John Hewitt, 1772, citing CO 5/545, The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, UK.

“General Account of sundry expenses incurred for Indians from the 25th June 1773 to the 24th June 1774,” database with images, Colonial America (https://www.colonialamerica.amdigital.co.uk/ : Accessed 14 Dec 2020), entry for John Hewitt, 25 Jun 1773, image 1, page 56; citing CO 5/554, The National Archives of the UK, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, UK.

“Petitions and memorials submitted to the Lords Commissioner,” database with images, Colonial America (https://www.colonialamerica.amdigital.co.uk : Accessed 14 Dec 2020), entry for Public Works, 1 May 1772, image 8, page 59; citing CO 5/545, The National Archives of the UK, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, UK.

Florida, “Spanish Land Grants,” database with images, FloridaMemory (https://floridamemory.com : accessed 3 Dec 2020), entry for Martin Hernandez (Confirmed), 1828; citing S 990, Box 17, Folder 21, Territorial Florida 1821-1845.

American State Papers: Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United States. United States: Gales and Seaton, 1860.

United States Congress, American State Papers Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United States, Part 8, Volume 6 (Washington, DC : Gales & Seaton, 1860) 60, 68, 71, 113; digital images, Google Books (https://books.google.com : accessed 17 Dec 2020).

Historical Records Survey, Work Projects Administration, Spanish Land Grants In Florida: Briefed Translations From the Archives of the Board of Commissioners for Ascertaining Claims And Titles to Land In the Territory of Florida (Tallahassee, Florida : State Library Board, 1940-41) 250; digital images, HathiTrust (https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uva.x001131477 : 29 Dec 2020).

Sherry Johnson, ed., “500 Years of Florida History – The Eighteenth Century,” The Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 93, No. 3 (Winter 2015); digital images UCF Digital Collections (https://ucf.digital.flvs.org : 20 Dec 2020).

Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org), “Adams-Onís Treaty,” rev. 20:56, 11 Dec 2020.

Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org), “Peace of Paris (1783),” rev. 23:16, 23 Dec 2020.

Recent Comments